In Australia, we are currently in the midst of unprecedented bushfires which are having a devastating impact on regional communities, our wildlife and our farm animals (with an estimated 500 million animals thought to have died) and 10.7 million hectares of bush, national park and farmland destroyed.

While the terrestrial impact of these fires is well documented in the media, there is often only a short lag before the marine environment encounters similar challenges. Marine heatwaves are defined as a period of warm water that lasts five days or longer, where temperatures are in the top 10% of events typically experienced in that region.

These are not a new phenomenon – the MSC certified Western Australian Abalone fishery is still trying to find its feet after the 2011 marine heatwave and is subject to conditions to rebuild commercial stocks. However, with increasing climate volatility, these heatwave events are now happening more frequently and with more ferocity.

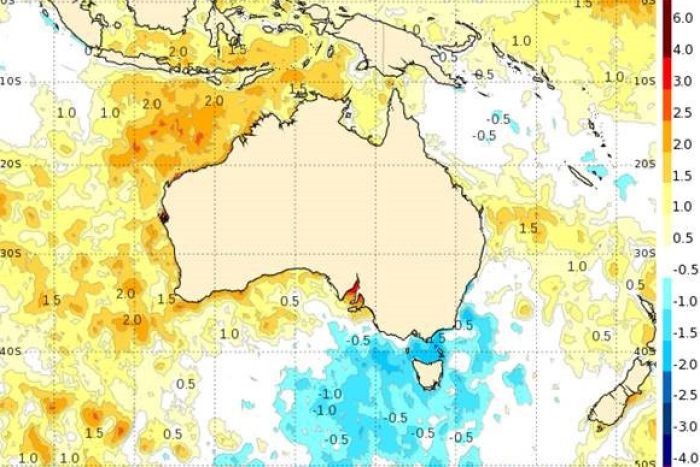

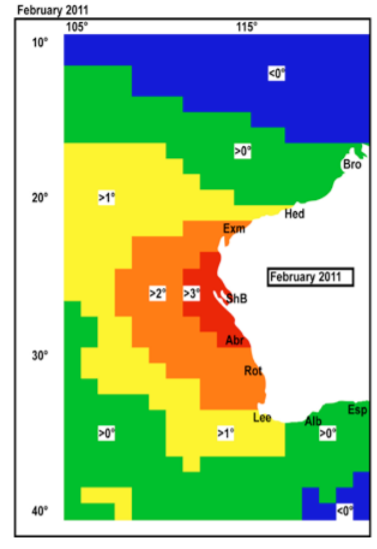

Monthly Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomalies in the south-eastern Indian Ocean (Western Australian coastline) in February 2011.

Source: Taken from Pearce and Feng, 2013.

Marine Heatwaves and increased environmental variability is a new challenge for fish, fishers and policy makers. Some marine species can move out of an area when they encounter unfavourable conditions, and in Australia at least, it can lead to a southerly shift in range for tropical species. We’ve recently seen sea snakes in the Southern Ocean and whale sharks much further south than expected. Other species stand to benefit from marine heatwaves. Whilst the abalone fishery suffered immensely with no anticipated recovery expected in areas closest to the heatwave, the king prawn fishery witnessed a positive impact from the warmer waters.

For those species like abalone and scallops who cannot escape the warmer water, the animals can become stressed and will eventually die if the heatwave is prolonged. In the northern reaches of the Western Australian Abalone fishery, a 99% mortality rate was observed with no recognisable recovery encountered nine years on. Commercial fishing has ceased entirely so the accompanying socio-economic impact is just as worrying.

The reason behind the lack of recovery in this fishery was threefold:

- A loss of protective habitat where abalone used as source of feed (abalone eat seaweed) and to hide from predators,

- The death of the local abalone population,

- The abalone in this area were already at the upper end of their temperature range meaning few abalone were prepared to live life on the edge.

Researchers are now looking to stimulate a recovery by bringing in abalone from hatcheries to give the population a boost and one day in the distant future, commercial fishing may once again return to this area of the fishery.

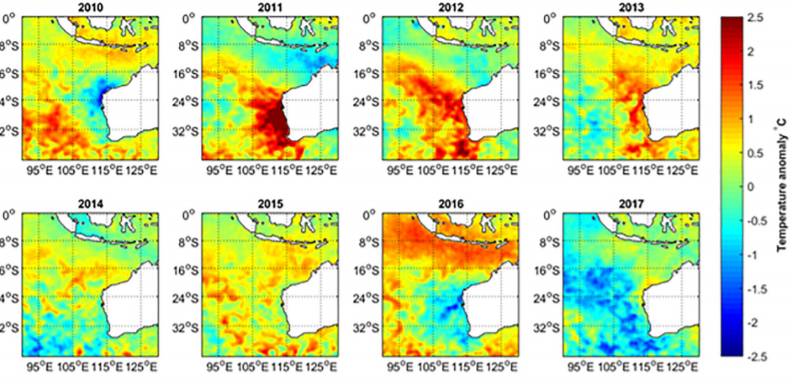

February–March (peak summer months) average sea surface temperature anomalies in 2010–2017, relative to the long-term mean temperature during 1981–2017.

Source: Taken from Caputi et al., 2019

Environmental variability is challenging for everyone, but it is likely to become the new normal. Dealing with this variability in the oceans from within an MSC certified fishery now should hopefully offer some level of protection to both fish and fishers. Why? Because it allows for management decisions to be more adaptive to such changes, requires rebuilding strategies to get fisheries back to healthy levels and needs collaborative decision making to get there.

The MSC is also looking at dynamic fisheries within the Fisheries Standard Review, which is asking questions about the best approach for fisheries that encounter and are vulnerable to highly variable ecosystems.

You can read more about the current Australian marine heatwave in this recent ABC news article, or find out more information about the 2011 marine heatwave in this paper authored by Western Australian fisheries scientists.