By Andrew Bowman

Stretching 771,000 km2 across Australia’s northern coast, the Northern Prawn Fishery covers three states and an enormous expanse of water. Yet only around 8% of this area is actively fished. It hasn’t always been this way - for decades the fishery has been downsizing, with significant reductions in the number of vessels, the amount of unwanted bycatch, and the amount of available fishing time.

Fishery name

Australia Northern prawn

Species fished

White banana prawn, red leg banana prawn, Brown tiger prawn, Grooved tiger prawn, Blue endeavour prawn, Red endeavour prawn

Gear types used

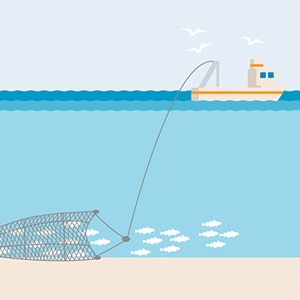

Bottom trawls (otter trawls)

The fishery was certified to the MSC Fisheries Standard in 2012, becoming the world’s first certified sustainable tropical prawn fishery. But its history of efforts towards sustainability and of care for the environment in which it operates began long before then.

Less fishing, more prawns

In 1966, just two boats fished for prawns in Northern Australia. An abundance of prawns and a huge appetite for them, meant this grew to around 200 vessels by 1970. By the 1980s there were 300. Since 2007, however, only 52 vessels have been granted licences to operate in the fishery.

If the stereotype that Australians love to eat prawns holds true, it’s also the case that they would like the tradition to last. In the 1980s it started to look like this hope might be in peril. Banana prawn catch peaked in the mid-70s and by the mid-80s tiger prawns were in trouble too. Recruitment (young prawns reaching maturation) in the stock was in decline and action was needed.

In 1985 a buy back scheme was introduced to reduce vessels numbers. In 1987 a mid-season closure and stringent gear restrictions were introduced to allow for tiger prawn recovery, and by 1993, the number of fishing licences had reduced to 132. This was all part of a long journey on sustainability: by the time the fishery was first certified in 2011, two of the five species’ stocks received the highest possible scores when assessed against the MSC Standard. And while the fishery has been certified as sustainable for over a decade, it continues to innovate and improve in practice.

“As Australia’s largest wild prawn fishery, we have a responsibility to look after the marine environment – we consider ourselves as stewards of the ocean.”

CEO, Northern Prawn Fishery Industry Pty Ltd.

Bycatch reduction

Covering such a vast region, the Northern Prawn Fishery’s fishing grounds are home to much more than just prawns. And the most efficient way of catching those prawns – trawling – comes with the hazard of catching other species.

Long before their MSC assessment, the fishery implemented their first – and Australia’s first - Bycatch Action Plan in 1998. The first concern was turtles - a species at particular risk as they drown if held underwater too long.

The fishery started trialling Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs), which use bars placed within the structure of the trawl nets to prevent large animals reaching the “cod-end” where catch is retained. An opening adjacent to the grid acts as an escape hatch. Following the adoption of these devices, research later reported a 99% reduction in turtle bycatch.

-copy-912.tmb-large1920.jpg?Status=Master&Culture=en&sfvrsn=cd4e4e81_1)

While turtle interactions vary greatly across the Northern Prawn Fishery, TEDs were made mandatory for all vessels by 2000. They have also proved to reduce unwanted catch of other large species like sharks and stingrays, which if retained can damage the prawn catch as much as themselves.

Soon after, obligatory implementation of additional bycatch reduction devices (BRDs) for smaller species was introduced.

From TED to Tom: innovation against bycatch

In 2015, a new three-year plan - the NPF Bycatch Strategy 2015-2018 - was voluntarily drawn up and implemented by NPF industry and supported by management. Its aim was ambitious: to reduce small fish bycatch by 30% within three years. Having already deployed standard trawling BRDs, the fishery harnessed partnerships with scientists and engineers to develop, adapt, and improve devices.

Working with the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) and CSIRO (the national science agency), the fishery trialled three new kinds of “fisheye” devices against their existing mesh panel BRDs. Like the other devices, fisheyes are integrated into the trawl nets. Their flattened cone shape creates a small area of lower water pressure that small fish are attracted to for shelter. Once inside, the fish can escape through the top.

Of the three devices trialled, the “Tom’s fisheye” initially seemed the least promising, but one bright idea changed everything. With the addition of a simple back plate, the re-trialled device logged an impressive 44% reduction in bycatch, with zero loss of the valuable prawns. In 2020 every vessel in the NPF was fitted with the Tom’s fisheye.

The latest challenge: Sawfish

While the fishery has had enormous success in reducing bycatch, one animal remains difficult to avoid: sawfish. Five species of this unusual ray exist in the world and four of those can be found in Australia’s northern waters. All species feature on the IUCN Red List of threatened species and are particularly susceptible to fishing.

As MSC Senior Fisheries Manager, Matt Watson explains, “It’s really hard for fishers to modify their fishing gear to prevent sawfish entanglements due to their unique long toothed rostrum or ‘saw’. From hand-set nets to prawn trawlers, sawfish species are vulnerable to interactions with fishing gear.”

But modification and innovation are now familiar territories for the NPF, which is once again diving into research. Partnering with Charles Darwin University and CSIRO, and with a grant from the Ocean Stewardship Fund, the fishery is working to protect sawfish by reducing interactions.

Mitigation proposals have included the use of electromagnetic fields and underwater lights that might alert the sawfish to approaching nets. Unfortunately, neither of these options has been effective - NPF industry is now trialling new innovative BRD designs and different gear/mesh types as potential mitigation solutions.

Whatever the case, the fishery has a wealth of data to help it towards a solution. With long established on-board scientist and crew observation programs, they know the sawfish species interacted with, when, where, by which vessels and with which type of gear. A key component of the OSF project is analysis of that data to better inform new and innovative gear designs.

Given the NPF’s demonstrable commitment to sustainable solutions, there’s good reason to think the project will deliver results for both sawfish and the fishery, and potentially help other fisheries reduce bycatch. The sawfish project is due for completion in April 2024 with its reporting becoming publicly available later in the year.