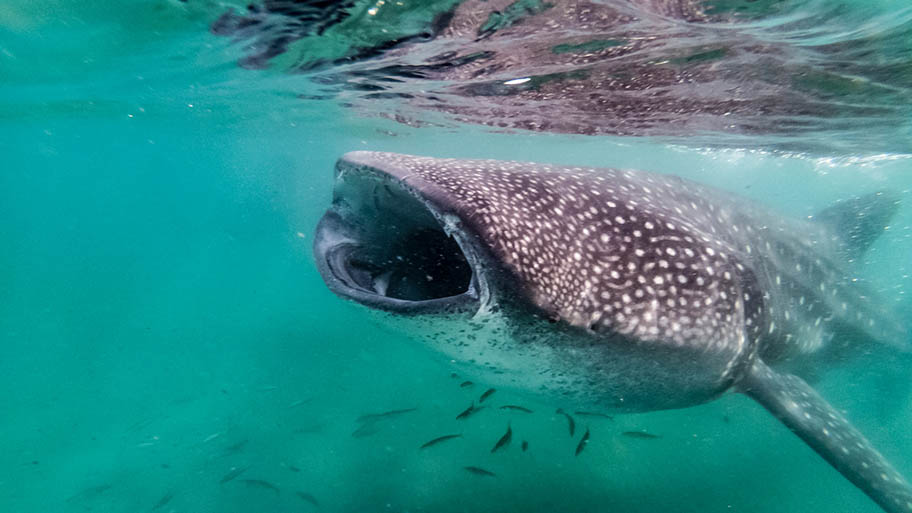

If you think tracking home deliveries is impressive, imagine doing it for a twenty-ton shark in the middle of the ocean.

When scientists tagged “Anne”, a whale shark in the Pacific Ocean near Panama’s Coiba Island, little did they know she would set a record for the longest distance ever registered by such a creature. Anne clocked up a staggering 20,142 kilometres (12,516 miles) over 841 days in a journey that took her to the Galapagos Islands and across the Pacific towards Japan and the Philippines.

Understanding where marine creatures go (and when and why) is no easy task but it's essential if we want to properly manage fish stocks.

Fortunately, new technology is aiding scientists to track species in close to real-time, providing a window into the hidden lives of some of the most elusive species.

Information revealed from tagging projects can help safeguard future fish stocks in oceans facing increasing threats, such as overfishing and climate change.

How are fish tracked?

“There’s a variety of tracking methods that can be used to monitor individual fish” explains Dr Florencia Cerutti, Accessibility Manager at the MSC. “One of the most basic methods is using a plastic tag attached to the fish with a unique number on it, much like an ear tag that farmers might use on cattle. This can help scientists understand basic biology such as how a fish grows or how far they travel.”The effects of tagging on an animal’s welfare must always be considered by the scientists, with trial research often used and Animal Welfare Ethics Committees involved to ensure impact is limited.

Space technology

Over the last 20 years, tagging technology has advanced with satellite and acoustic devices available to scientists studying the oceans.Satellite tags such as SPOTs (Smart Positioning or Temperature Tags) can capture a range of data every few minutes, transmitting close to real-time data whenever the fish breaches the surface.

Acoustic tags work in pairs with a tag on the animal and a receiver nearby providing check points as the fish swims past. They can help to identify sensitive habitats used for potential breeding sites, where a population might be more vulnerable to fishing impacts.

The devices have helped discover the first ever nursery of baby great white sharks off the coast of New York and find remote foraging grounds for leatherback turtles in the North Atlantic.

Social media sharks

You can even follow some sharks – literally – on Twitter, thanks to dedicated scientists sharing close to real-time shark movement data.“These types of tags help us understand how animals undertake long-distance migrations or where they interact with certain habitats or fisheries” says Dr Cerutti. “For migratory animals like tuna or sharks, international collaboration between scientists means you can start to see how these predators move across ocean basins and borders. This is vital when managing the stocks of highly migratory species.”

Conducted properly, fish tagging can provide information on population size, growth, habitat use, movement patterns, seasonal variations, harvest levels and mortality rates. This information can be vital for maintaining healthy fish stocks.

Playing tag with giant rays

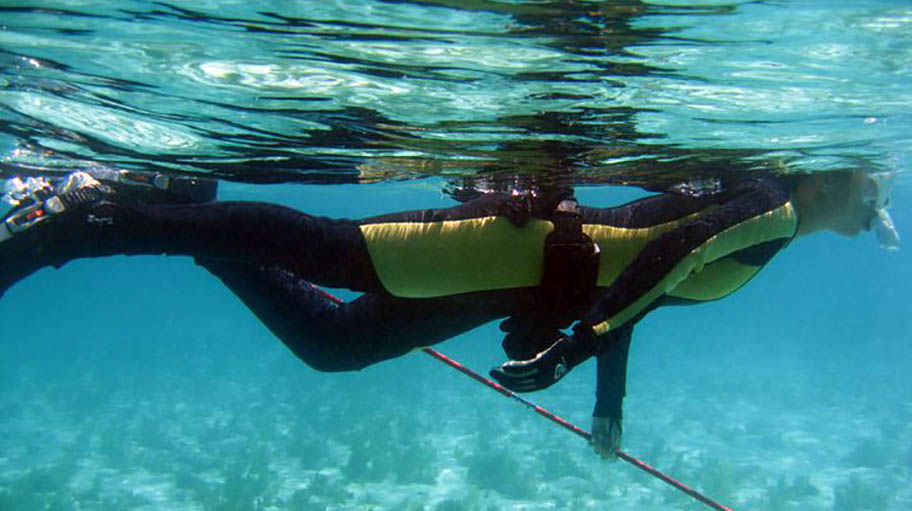

Tags can be attached onto the body or fin of a fish, or even through an implant. Trained scientists can immobilise sharks and rays by turning them upside down. This slows down their metabolism and puts them into a state called tonic immobility. They can hold the animal by the side of the boat as they carefully implant the tag upside down or keep them upright and attach a tag to their fin.Other animals that are more difficult to catch, like a hammerhead or whale shark, are often tagged using a speargun or Hawaiian sling (a manual version) by a free diver underwater. “You have to hope you’ve got good aim” explains Dr Cerutti. “I’ve tagged manta rays five metres wide before. It’s an incredible experience but takes a couple of goes before you get it right. On the other hand, implants take a long time to perfect – I trained using an orange and progressed onto pork meat!”

Dr Florencia Cerutti freediving to tag marine species © Charles Darwin University

How tagging helps conservation

Tagging is often one strand of a much larger project looking to solve a particular issue facing a fishery or species. Several of our Ocean Stewardship Fund projects this year are hoping to use tagging data to support further sustainability improvements in MSC certified fisheries.Protecting the Greenland shark

Windsor University in partnership with MSC certified Greenland Halibut Fishery will commence on a tagging project on the Greenland shark. The species is the world’s longest living vertebrate, with some found to be at least 400 years old. That gives them plenty of time to encounter fishing fleets, making them particularly vulnerable to bycatch.Currently, little is known about the survival rates of Greenland shark once they are caught and returned to the ocean. So, the team of scientists will use a state-of-the-art tagging technology called Pop-Off Satellite Archival Tags (PSATs), to help assess the mortality rate and provide vital data for improving the fishery.

Tagging Greenland shark © Hussey Lab

Tagging Greenland shark © Hussey Lab