From mapping seabed floors for vulnerable habitats to trialling innovative wildlife bycatch reduction devices, fisheries play a key role in collecting data that can better protect marine biodiversity. We highlight the achievements of sustainable fisheries that are driving real change in our oceans.

Australian Northern Prawn Fishery vessel © Dylan Skinns / Austral

Australian Northern Prawn Fishery vessel © Dylan Skinns / Austral

Fishing is one of the key contributors of biodiversity loss in our oceans, from depleted stocks through overfishing to species caught as bycatch. Fisheries around the world face these challenges every day while working hard to feed us and support livelihoods and families. But collaborations between scientists, governments and the fishing industry are delivering innovative solutions to mitigate impacts and drive reform.

A 99% reduction in turtle bycatch

Based off Australia’s northern coast and covering 771,000 square kilometres of tropical waters, the Australian Northern Prawn Fishery has been driving sustainability initiatives since the 1990s. The fishery has virtually eliminated accidental turtle bycatch with interactions down by 99% by using Turtle Exclusion Devices (TEDs). TEDs act as sorting grids, allowing prawns to be kept while turtles can swim out of the nets unharmed. Adopting TEDs is just one way the fishery has demonstrated its sustainability, helping it to achieve MSC certification in 2012.

“As Australia’s largest wild prawn fishery, we have a responsibility to look after the marine environment”, says Annie Jarrett, CEO of the Northern Prawn Fishery Industry Pty Ltd. “Since certification, we’ve made continual improvements in order to meet the world’s best practice for fisheries and sustainability management.”

Some of those ongoing improvements include encouraging local operators such as Raptis Seafoods and Austral Fisheries to develop, test and implement new bycatch reduction devices, effectively reducing bycatch rates by 44%. This has helped further minimise interactions with vulnerable species such as sea snakes.

Other species like sawfish, however, remain susceptible to interactions with fishing gear so research continues. “It’s really hard for fishers to modify their fishing gear to prevent sawfish entanglements due to their unique long toothed rostrum or ‘saw’,” explains Matt Watson, MSC Senior Fisheries Manager in Australia. “From hand-set nets to prawn trawlers, sawfish species are vulnerable to interactions with fishing gear. This is why it’s important industry and scientists work together to find solutions.”

Recognising the need to make improvements to their operations to minimise interactions with endangered sawfish species, the Northern Prawn Fishery is working alongside researchers at Charles Darwin University and CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australian Government) to develop effective solutions.

One proposal involves the use of electromagnetic fields to see if sawfish can be alerted to the net in advance, giving them time to flee. Fishers onboard also collect tissue samples for genetic studies and use underwater cameras to see how gear can be modified.

Sustainable fishing drives research and innovation

When fisheries are assessed against the MSC Fisheries Standard, one of its key components is how the fishery’s operations may impact the wider ecosystem. Most fisheries that gain certification are often given ‘conditions of certification’. These are improvements the fishery must make or risk suspension from the MSC Program.

During the certification of the Cornish hake gillnet fishery, assessors suggested stronger data was required to show the fishery was managing impacts on local marine populations. The fishery was given a condition to implement a management strategy to reduce interactions with endangered, threatened or protected species.

The fishery successfully closed this condition within two years of certification by introducing ‘pingers’ or acoustic deterrent devices on its nets, increasing data collection through fishery observers and complying with European Commission legislation. Pingers work by sending underwater acoustic waves that signal to marine mammals that nets are in the water and thus prevent entanglement. Legislation in the UK requires all fishing vessels more than 12 metres fishing in specific locations and using certain gear must be fitted with these devices. The Cornish hake gillnet fishery, however, has made pingers mandatory for all vessels – even those not required by law. Through the use of pingers, the fishery reduced bycatch of harbour porpoise by 80% and in 2019 reported zero interactions with marine mammals.

Banana pinger in use © Fishtek Marine

Banana pinger in use © Fishtek Marine

Recent research from Cornwall Wildlife Trust and the University of Exeter conducted trials of an acoustic pinger called the ‘Fishtek Marine Banana Pinger’, developed by Fishtek Marine Ltd. Their most recent research collaboration involved an eight-month long study on porpoise that found no decrease in effectiveness.

Cornwall Wildlife Trust Conservation Manager, Ruth Williams, explains: “The results show that there is a practical solution that is both effective and does not impact or change the animals' behaviour – a positive result for both conservation and fishermen alike."

Identifying endangered species through a smartphone app

It is not only species but also habitats and ecosystems that are considered during MSC assessments. But with only a fifth of the ocean seabed floor mapped by scientists, much is still unknown about vulnerable marine habitats.

The Denmark Skagerrak and the Norwegian Deep cold-water prawn fishery contributed to changing that in 2018. It implemented an ocean code of conduct and a comprehensive guide to help fishers identify different corals and deep-sea sponges. All vessels were required to provide data on incidental captures of endangered, threatened or protected species and any interactions with certain indicator species of sensitive habitats. A better picture of where sensitive habitats might occur was built using the data. This data now helps vessels avoid these areas with coordinates provided on the Danish Fishermen Producers Organization (DFPO) website.

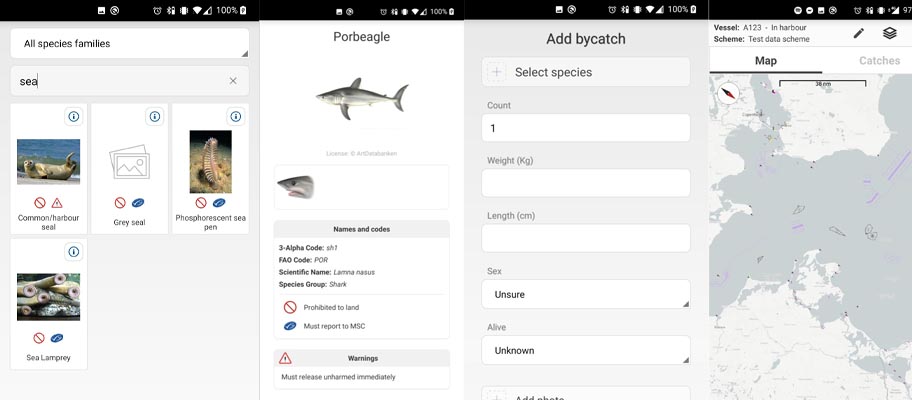

The fishery has since merged with a multinational group of fisheries – that includes 15 separate stocks – under the Joint Demersal Fisheries in the North Sea. These fisheries alongside VisNed – a Dutch fishing association – are further contributing to science by developing a mobile app that helps fishers identify and log interactions with endangered species. The project was awarded £50,000 through the MSC’s Ocean Stewardship Fund in 2020 to support the app’s development.

“In our experience, reliable and sustained registration of endangered, threatened and protected species is challenging and requires constant attention,” explains Wouter van Broekhoven, former Chief Scientist at VisNed. “It can be time consuming; fishers can misidentify species and lists can get lost on board rendering the data entry unusable because of water damage.

“Ocean science is entirely dependent on good quality data, and we believe the app will allow a big improvement in quantity and quality of the data on endangered species interactions.”

VisNed smartphone app screenshots © VIsNed/Mads Dueholm

VisNed smartphone app screenshots © VIsNed/Mads Dueholm

Striving for a sustainably harvested and productive ocean

Ensuring well managed fisheries and seafood that is sustainably harvested requires oceans and the marine biodiversity in them to be more resilient and productive.

The United Nation’s Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development launches later this month and calls for greater collaboration and data sharing across the marine sector.

It is only through science, industry and governments working together that our oceans will support life under the water - as well as life on land - far into the future.